Collections and Scales

Folk, pop, classical, and modern composers often organize pitch materials using scales other than major and minor. Some of these scales, like the various diatonic modes and the pentatonic collection, are relatively familiar to most listeners. Others — such as octatonic, whole-tone, and acoustic collections/scales — are more novel, and usually (but not always) found in twentieth- and twenty-first-century compositions.

When characterizing many of these new musical resources, the word “collection” is often more appropriate than “scale.” A collection is a group of notes — usually five or more. Imagine a collection as a source from which a composer can draw musical material — a kind of “soup” within which pitch-classes float freely. Collections by themselves do not imply a tonal center. But in a composition a composer may establish a tonal center by privileging one note of the collection, which we then call a scale.

Diatonic Collection (modes)

The diatonic collection is any transposition of the 7 white keys on the piano. Refer to these collections by the number of sharps and flats they contain: the “0-sharp” collection, the “1-sharp” collection, and so on. The “2-flat” collection, for example, contains the pitch classes {F, G, A, B-flat, C, D, E-flat}.

When these collections gain a tonic note, they morph into scales, which by tradition we name according to the “modal” system established in centuries ago. (Note that while these modes share their names with the modes of the Medieval Christian church, they function quite differently. The similarity is principally one of name.)

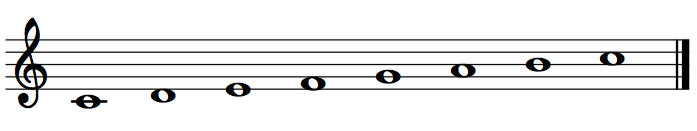

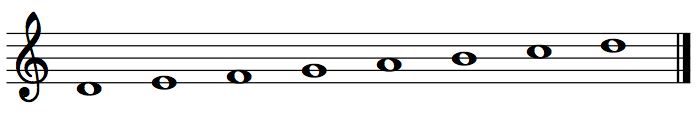

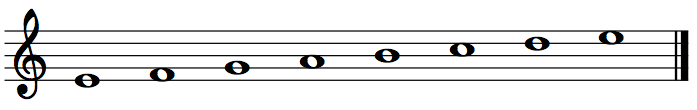

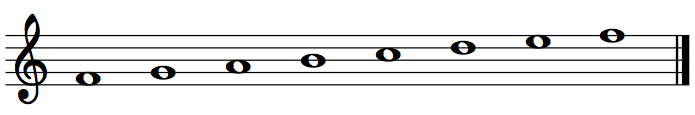

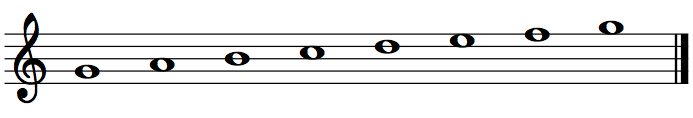

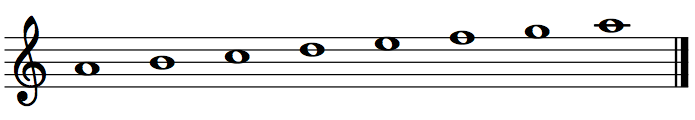

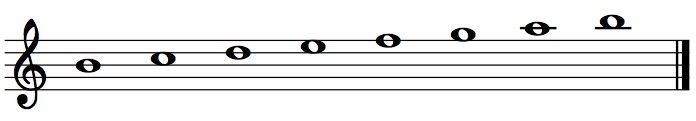

One way to look at these “modes” is to think of the seven white keys of the piano {C, D, E, F, A, B}. These notes, when starting on different pitches, create the different modal scales. By taking each note of the seven-white-key collection, and treating it as as the tonic, all seven modal scales can be played. Ionian treats C as tonic, Dorian treats D as tonic, Phrygian treats E as tonic, Lydian treats F as tonic, Mixolydian treats G as tonic, Aeolian treats A as tonic, and Locrian treats B as tonic:

Ionian mode (major scale): do re mi fa sol la ti do

Dorian mode: do re me fa sol la te do

Phrygian mode: do ra me fa sol le te do

Lydian mode: do re mi fi sol la ti do

Mixolydian mode: do re mi fa sol la te do

Aeolian mode (natural-minor scale): do re me fa sol le te do

Locrian mode (uncommon outside jazz): do ra me fa se le te do

Like the major and minor scales, these intervallic relationships can be transposed to any tonic pitch.

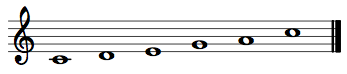

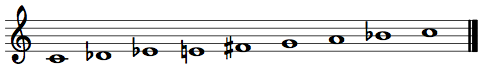

Pentatonic Collection

Pentatonic collections are five-note subsets of the diatonic collection. Here’s a quick way to create a pentatonic collection: (1) List the notes of a major scale. (2) Remove scale degress 4 and 7. (E.g., the pentatonic collection {C,D,E,G,A} corresponds to scale degrees 1,2,3,5,6 of the C major scale.)

Removing scale degrees 4 and 7 results in a collection with no half steps. As a result of its “halfsteplessness”, any member of the collection easily functions as a tonal center. For example, given the 0-sharp pentatonic collection, there are five unique scales formed when each of the collection’s pitch classes become a tonic: C pentatonic (C,D,E,G,A), D pentatonic (D,E,G,A,C), E pentatonic (E,G,A,C,D), and so on.

The black keys on the piano also form a pentatonic collection:

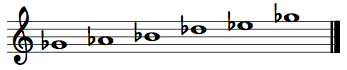

Whole Tone Collection

This is a group of notes generated entirely by whole tones: {0,2,4,6,8,10}, for example.

There are only two unique whole-tone collections. WT0 contains pitch classes {0,2,4,6,8,10}, while WT1 contains pitch classes {1,3,5,7,9,11}. In other words, WT0 contains the pitch classes {C, D, E, F-sharp, G-sharp, B-flat}, while WT1 contains pitch classes {C-sharp, D-sharp, F, G, A, B}.

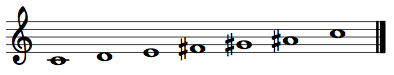

Octatonic Collection

Called octatonic because it has eight pitch classes, the octatonic collection is full of compositional potential and has been used by many composers to a variety of ends. An octatonic collection is easily generated by alternating half steps and whole steps. Using pitch class numbers, one example is {0,1,3,4,6,7,9,10}.

The interval content of this collection is very homogenous, and this intervallic consistency leads to one of its most interesting properties. When we transpose the above collection by 3—adding 3 to each of the integers in the collection—{0,1,3,4,6,7,9,10} becomes {3,4,6,7,9,10,0,1}. Comparing the two shows that these collections are exactly the same! In fact, you would come up with the same collection if you transposed it by 6 or 9 as well.

Olivier Messiaen called such collections “modes of limited transposition.” (The whole-tone scale is also a mode of limited transposition.) And as a result of the property, there are only three unique octatonic collections. We name these arbitrarily as OCT(0,1), OCT(1,2), and OCT(2,3). The numbers to the right of “OCT” are pitch classes within that scale. (E.g., the {0,1,3,4,6,7,9,10} collection I discussed above is OCT(1,2).) We can also call them C–C♯ octatonic, C♯–D octatonic, and D–E♭ octatonic.

Other Collections and Scales

There are many, many other collections and scales used by composers and musicians in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. Messiaen, for example, described five more modes of limited transposition, and there are other smaller collections that have the same property. Acoustic scales, formed from the first seven unique partials of the overtone series, are common in the music of Debussy, Bartok, and Crumb — ocassionally as a representation of nature. Jazz musicians have an entire set of scales used for improvisation. Non-Western musics often have unique systems of scales and collections, such as the rāgas used in Indian classical music.

More generally, any large set of pitch classes that form the basis for a passage may function as a collection, even if it has no familiar name. Most often, music theorists refer to these collections with pitch-class set notation.

This resource was created by Brian Moseley and contains contributions from Meredith Cahill, Elise Campbell, and Kris Shaffer.