Basic Git Workflow

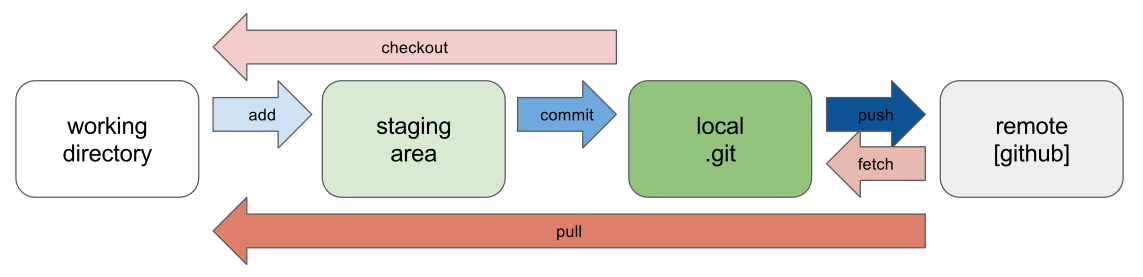

In general, the basic routine is,

Update your local repository with:

git pull (or grab a new copy with git clone)

Edit the files and folders locally, then:

git add...

git commit...

git push...

Let’s walk through the basic commands!

Always remember: Git has good built in help, so add

--helpto any command to learn more.

git clone

To download a copy of a repository from GitHub, use git clone.

Go to the test GitHub repository you created during the last step, click the green “Clone or download” button, and copy the URL.

In your terminal, navigate to your desired location (I suggest a folder named “GitHub” in your Documents directory).

Type git clone and paste in your URL (right click or shift+Ctrl+V).

For example:

git clone https://github.com/uidaholib/git-example.git

Clone will download a full copy of the repository to your local machine and record its origin on GitHub.

This ensures there is a connection so you can push your changes to GitHub or fetch updates.

Your cloned repo is simply a folder of files, with a hidden .git directory that stores the full history.

The .git folder is hidden for a reason–you don’t need to know anything about it!

The rest of the directory is the same as any other folder on your computer.

You can edit, create, delete, or move files just as you normally would–but now Git is watching!

git status

Git status is your friend. Type it often!

git status

Create a new file in your repository using a text editor, or the command line:

echo "some interesting notes" > notes.txt

Then check the status again!

git add

Once you have made changes in your repository, you need to tell Git to start tracking the file.

The function git add adds the files to the “staging area”, meaning Git is now tracking the changes.

git add notes.txt

git status

Files can be added individually by name, or use the flag git add -A to stage all currently changed files at once.

Only the changes to files in the “staging area” will be saved in the next commit.

git commit

We changed a file, we added it to the staging area, and now we are ready to take a snapshot storing away these changes forever.

Let’s commit!

Each commit records the state of the full repository along with the timestamp, user name, email, and message of the committer.

A message is required!

It is your note to posterity so you can remember why you made changes in the future (for style tips, see The Art of the Commit).

git commit -m "add notes file"

git status

We have stored away a new version of the documents in the repository and will be able to navigate this history. Typically, it is better to make many smaller focused commits, rather than big ones, since small changes will be easier to undo, review, and merge.

The

-mflag adds the message on the command line. If you do not include a message, Git will open your default text editor and wait for you to enter and save a message.

Repeat!

You will use add, commit, and status over and over!

Git add fills the staging area.

Git commit takes the snapshot of changes in the staging area.

Edit a file in your test repository and repeat the routine.

git add notes.txt

git commit -m "more notes"

git status

git push

Notice that git status now says “your branch is ahead of origin/master”.

Origin/master is the standard way to name the main branch of the remote repository.

We finished our changes to the repository locally, now we want to add them to the remote hosted on GitHub using push.

git push origin master

Push sends only the changes, so it is very efficient network use.

Using origin master specifies which branch we want to push to in the remote repository.

However, in most cases the command can be shortened to just git push.

Review

git status

git pull

git add file.txt

git commit -m "message"

git push

Depending on your workflow, you may want to

git fetchrather thanpull.git fetchupdates repository from remote, but does not change the local files.git pullis short forfetch+merge, thus will update from the remote and combine that new information with your local work.