Chapter I.

OF THE HALL OF SULNEY AND HOW SIR YWAIN LEFT IT.

SIR YWAIN sat in the Hall of Sulney and did justice upon wrong-doers. And one man had gathered sticks where he ought not, and this was for the twentieth time; and another had snared a rabbit of his lord’s, and this was for the fortieth time; and another had beaten his wife, and she him, and this was for the hundredth time: so that Sir Ywain was weary of the sight of them. Moreover, his steward stood beside him, and put him in remembrance of all the misery that had else been forgotten.

And in the midst of his judging there was brought into the hall a child that had been found in the road, a boy of seven years as it seemed: and he was dressed in fine hunting green, but not after the fashion of that day or country. Also when they spoke to him he answered becomingly, but in a speech that no one could understand.

So Sir Ywain had him set by the table at his own side, and now and again as he judged those wrong-doers, he cast a look upon the child. And always the child looked back at him with bright eyes, and even when there was no looking between them, he listened to what was being said, and smiled as though that which was weariness to others was to him something new and joyful. But as the hour passed, Sir Ywain felt his mind slacken more and more, and whenever he saw the boy smiling, his own heart became heavier and heavier between his shoulders, and his life and the life of his people seemed like a high-road, dusty and endless, that might never be left without trespassing. And though he would not break off from his judging, yet he groaned over the offenders instead of rebuking them; and when he should have punished, he dismissed them upon their promise, so that his steward was mortified, and the guilty could not believe their ears.

Then when all was said and done the hall was cleared, and Sir Ywain was left alone with the boy.

But the steward, looking slyly back through the hinges of the door, saw that his lord and the child were speaking together; and he perceived that they understood one another well enough, though how this should have come about he was not able to guess, having himself heard the boy answering to all questions in none but an outlandish tongue.

Then he saw Sir Ywain rise up, and suddenly he was aware that his lord was calling for him loudly and with a hearty voice, as he would call for him long since, when they were at the wars together. And when he went in, Sir Ywain bade him summon all the household.

Now when the household were come into the hall they stood at a little distance from the dais, in the order of their service, and Sir Ywain stood above them in front of the high table. And beside him was the boy, and before him was his own brother, who was now an esquire grown, with hawk on wrist.

Then Sir Ywain bade his brother kneel down, and there he made him knight, taking his sword from him and laying it on his shoulder, and afterwards belting it again round his body. And he took the keys from his own girdle and the gold spurs from his own feet, and said aloud: I call you all to witness that as I have done off my knighthood and the Honour of Sulney, and given them to this my brother Sir Turquin, so also by these tokens do I deliver unto him the quiet possession of my house and goods and the seisin of all my lands, to hold unto him and his heirs for ever, by the service due and accustomed for the same. And henceforth I go free.

Then his brother, who was both glad and sorry, and moreover was still in doubt how this might end, stood holding the keys and the spurs, and looking at him without a word. And he looked also at the child, and he saw that for all the difference in their years, the eyes of Sir Ywain had become like the boy’s eyes: and as he looked his heart became heavy, and for a moment he envied his brother and feared for himself. But in his fear he moved his hands, and the keys clanked and the spurs clinked together, and his heart leaped up again for joy of his possessions.

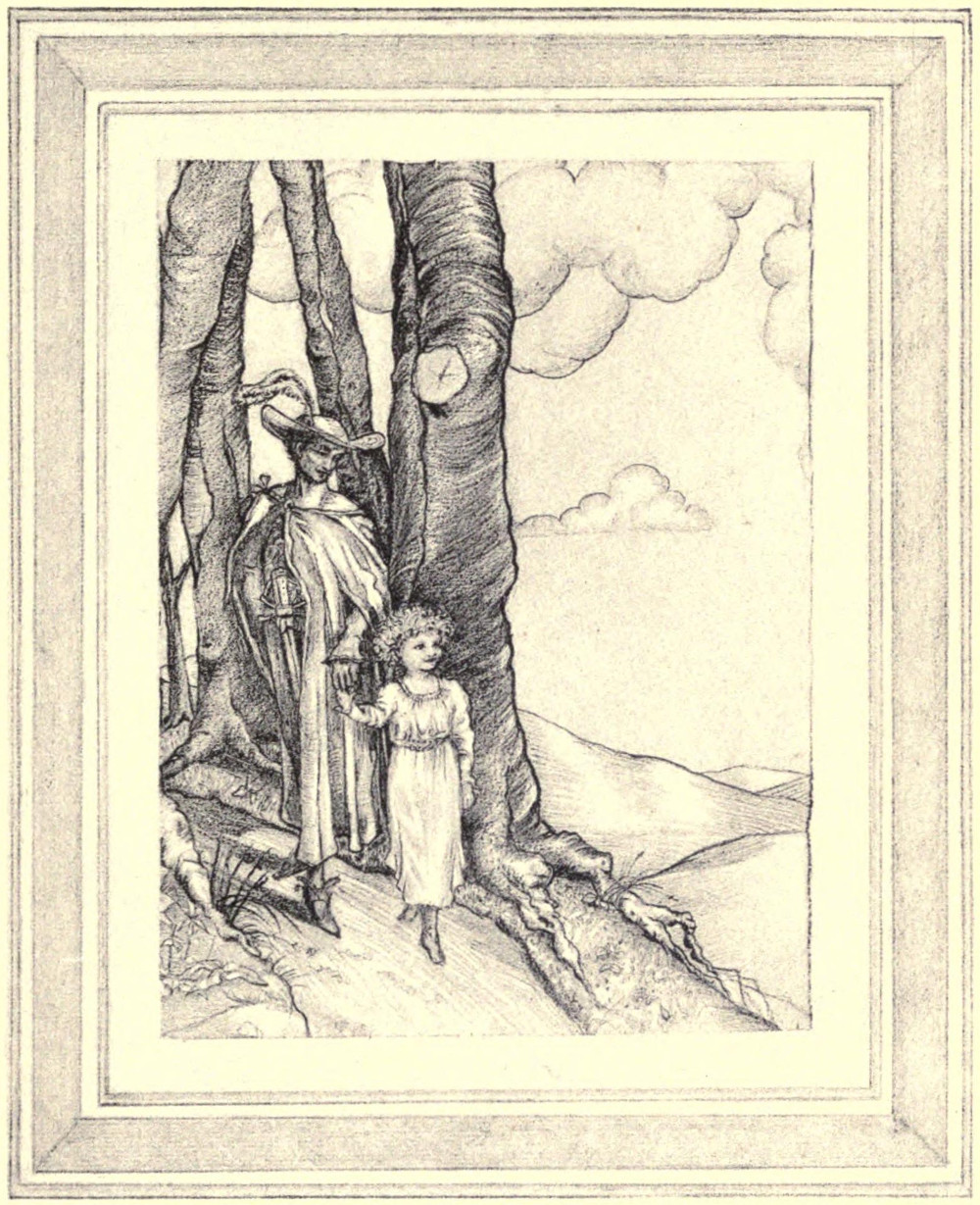

And all this Ywain saw as it were a great way off, and he smiled, and forgot it again instantly. And the boy took his hand, and they went down the hall together. And when they came to the door to pass out, the steward got before them and bowed as he was used to do, and he spoke very gravely to Sir Ywain, reminding him that this same afternoon had been appointed among the lords, his neighbours, for the witnessing of certain charters.

But Ywain and the boy looked at one another and laughed, and the steward saw that they laughed at the lords and at him and at the very greatness of the business: and he was enraged, and turned away and went to his new master.

Then Sir Turquin came hastily after them, and he laid his hand upon his brother’s arm and bent his head a little, and spoke to him so that none else should hear, and he said: What is this that you are doing; for no man leaves all that he has, and departs suddenly, taking nothing with him. But those two went from him without answering, and they passed, as it seemed, very swiftly along the road under the woodside, and were hidden from him. And again, as he stood still watching, he saw them going swiftly above the wood where there was no path, but only the bare wold before them.