Chapter XXII.

OF THE ADVENTURE OF THE HOWLING BEAST.

THEREAFTER Ywain continued in weariness, and in despite and anger against the great ones of Paladore: for he perceived how they had devised these adventures of a very purpose, so that they might have him at their will by fellowship or else by treason. Moreover he longed greatly to see his lady again, and could not: and of such longing also comes weariness, when a man sees time go by and nothing bettered. So Ywain made search in all Paladore, if he might but hear tell of the Lady Aithne: and he found some few that would speak of her, and little he got of them. For one would say how she was gone into a far country, and one how she was ever a wanderer: and thereby they intended no good thing, for their meaning touched on Aladore, howbeit they named not the name. So Ywain went to and fro, and returned continually to the house where he had seen her: and in a three days he came there twenty times, and at last he thought to lie like a dog before her doorway.

Then at this time Sir Rainald sent a messenger to him, and said how that in two adventures Ywain had done great pleasure to his lord the Prince, and he gave him to think that by the achieving of the third adventure he might well establish himself. And Ywain believed him not, for he knew better: but by reason of his despair he made assent: for he cared not what might become of him.

So upon the morrow very early two came and called him forth: and they brought him a horse and an axe, but no gear else, and he went with them apparelled in the cloak and hat of his pilgrimage. Then he asked them of the adventure, and they told him thereof: and the manner of it was that he should enter in a certain park and hew therein a tree: and the tree might be which he would, but he must hew it within a day and a night, and it must be down before the daybreak. And as for the hazard and the pain of the adventure, they said how that came by the howling of the Beast; for at the sound of the axe it would howl beyond endurance, so that none might hear it and be the man he was aforetime.

Now the park was from the city a two hours journey, and there was a high wall about it and a strong gate thereto: and there were some within which were appointed to keep the Beast, but they were all deaf men, and heard nothing in the world. So they that brought Ywain there unlocked the gate, and they gave him the axe and bade him enter quickly, for they were in haste to be gone. Then he left his horse and entered, and the gate was shut upon him, and he could well hear those men departing, for they rode as men in fear.

Then he looked and saw how the park was all full of thickets, very dark and tangled of old growth; and he went forward slowly, lifting high his feet. And as he went it bechanced that he struck his axe against a tree, and wounded it chipwise. And immediately there came a noise beside him like the growling of a great hound, and therewith a fear took him that was like a fear out of childhood, for it was quicker than thought and more deep within him. And he looked all ways, and saw nothing; and he listened and heard the beating of his heart.

Then he went forward again and found a place that was open ground: and it was a green valley between the thickets, and in the midst of the valley stood a goodly elm-tree. Yet was the goodliness of it by semblance only, for within bark it was long since gone and rotten. And Ywain came to the elmtree and struck it wilfully, for he was there in a clear field and thought to see the truth of the matter. But in his stroke his senses departed from him, for there came a noise behind him such as he heard never in all his days, no, nor dreamed thereof in an evil dream. For it was like the roaring of a wild bull and like the howling of a dog upon a grave: and when he heard it his life turned black within him and his heart was angered even to madness. And he swung his axe and struck the tree haphazard, as a man may strike that is blinded in battle, and his fear was greater than his courage, and his anger was greater than his fear.

So he went smiting, and his hands were bruised and his body shaken: and the Beast howled even more loud and the rage of it pierced Ywain’s heart and broke it utterly. For when he heard that sound it seemed to him that he was hated of all men and of himself also, and he felt his life perishing into dust as the grain perishes between the millstones. And his strength went from him momently, so that in no long time he had been mad or dead, save only for the help wherewith he was holpen presently.

For in his misery there came to him a sound of clear music, as a lantern comes to a child that is lost in darkness: and the music was of a reed only, yet there was within it a voice singing that was as plain as words. For as Ywain heard it he thought on old and noble wars, and he remembered in his heart the names of them which had renown therein; and he feared no more to be hated, for he had part with them. And therewith the howling of the Beast became faint and without meaning, as a noise that is very far off: and Ywain’s strength came again to him and he hewed with might and with measure, and in a hundred strokes he felled the tree endlong.

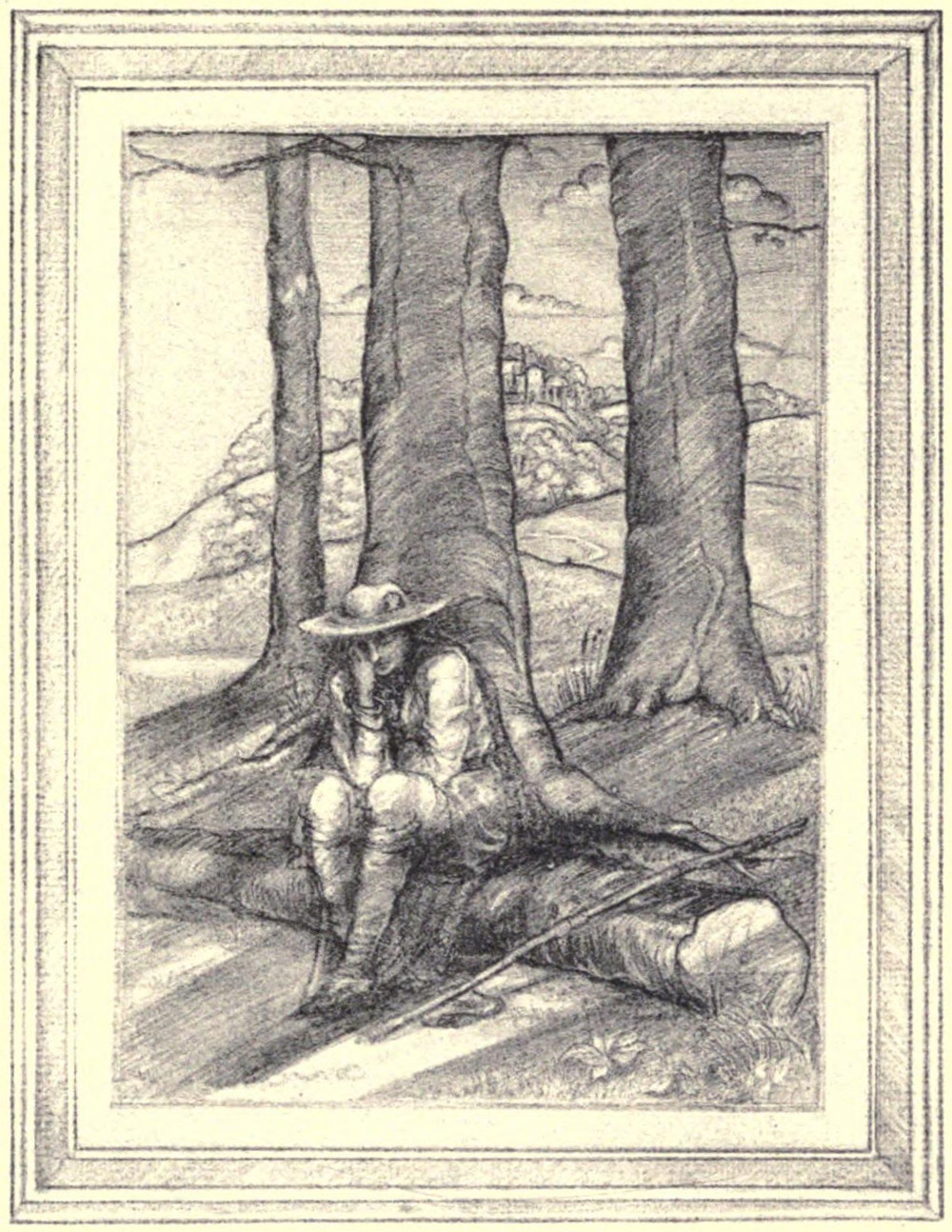

Then with the fall of that tree the noise of howling ceased, and Ywain looked and saw that he had been long in his madness, for it was now the last hour of the day. And the music that he heard ceased not, but the voice changed within it: for it sang no more of old things but of new. And as he heard it Ywain forgot all the ills that he had suffered in all his life, and he thought on such a place as might be the land of his desire: and it seemed to him that he was not far therefrom. Then his thought went from him and he slept.

And when he awoke it was grey dawn: and he rose up and began to go from that place. And as he went there met him a herd-girl with a herd of black swine, and in her hand was a little pipe of wood, and when Ywain saw the pipe he remembered how he had been holpen overnight. Then he thought to ask of the herd-girl what might be the music which had come to him. And she held up her pipe before him and said: Sir, there is here no music but of this only: for here are none but deaf men, and I that pipe to the deaf. But whither you go there is music enough: for you will go, as I think, by the high-road. And therewith she left him and went further. But as she went she looked again at him, and she smiled as with remembrance: and in her smiling he saw his lady the third time. Yet he saw her not to his profit, but as a man may see an image in a glass, which is certainly of the world visible, but in nowise of the life thereof. So he looked only and let her go from him.